[2025-jun-17] The SlackDocs Wiki has moved to a new server, in order to make it more performant.

Table of Contents

The X Window System

What Is (And Isn't) X

Eons ago computer terminals came with a screen and a keyboard and not much else. Mice hadn't come into common use and everything was menu driven. Then came the Graphical User Interface (GUI) and the world was changed. Today users are accustomed to moving a mouse around a screen, clicking on icons and running tasks with fancy images and animation, but UNIX systems predated this and so GUIs were added almost as an afterthought. For many years, Linux and its UNIX brethren were primarily used without graphics of any sort, but today it is perhaps more common than not for users to prefer their Linux computers come with shiny, flashy, clickable GUIs, and all these GUIs run on X(7).

So what is X? Is it the desktop with the icons? Is it the menus? Is it the window manager? Does it mark the spot? The answer to all these is a resounding “no”. There are many parts to a GUI, but X is the most fundamental. X is that application that receives input from the mouse, keyboard, and possibly other devices. X is that application that tells the graphics card what to do. In short, X is the application that talks to your computer's hardware for graphical purposes; all other graphical applications simply talk to X.

Let's stop for a moment and talk about nomenclature. X is just one of a dozen names that you may encounter. It is also called X11, xorg, the X Window System, X Window, X11R6, X Version 11, and several others. Whatever you hear it called, simply understand that the speakers are referring to X.

Configuring the X Server

Once upon a time, configuring X was a difficult and painful process that caused the magic smoke to come gushing out of hundreds of monitors. Today X is a lot more user friendly. In fact, most users will not need to configure X at all, Slackware will simply figure out all the proper settings on its own. There are, however, still some computers that X can't properly auto-configure and will need a little bit of work on your part.

Once upon a time, the X configuration file was located at

/etc/X11/xorg.conf, and if you create a file

there, X will honor whatever settings you place within it.

Fortunately, with X.Org 1.6.3 an

/etc/X11/xorg.conf does not even need to be

present for X to generate a working display.

If for whatever reason, you need to make configuration changes to X,

try to avoid using this file; it's antiquated and inflexible. Rather,

the /etc/X11/xorg.conf.d/ directory is where you

should put such tweaks. Any file you place within that directory will

be read when X starts up. This allows you to split-up your

configuration into more easily manageable parts. For example, here's

my /etc/X11/xorg.conf.d/synaptics.conf file for my

laptop.

darkstar:~$ cat /etc/X11/xorg.conf.d/synaptics.conf

Section "InputDevice"

Identifier "Synaptics Touchpad"

Driver "synaptics"

Option "SendCoreEvents" "true"

Option "Device" "/dev/psaux"

Option "Protocol" "auto-dev"

Option "SHMConfig" "on"

Option "LeftEdge" "100"

Option "RightEdge" "1120"

Option "TopEdge" "50"

Option "BottomEdge" "310"

Option "FingerLow" "25"

Option "FingerHigh" "30"

Option "VertScrollDelta" "20"

Option "HorizScrollDelta" "50"

Option "MinSpeed" "0.79"

Option "MaxSpeed" "0.88"

Option "AccelFactor" "0.0015"

Option "TapButton1" "1"

Option "TapButton2" "2"

Option "TapButton3" "3"

Option "MaxTapMove" "100"

Option "HorizScrollDelta" "0"

Option "HorizEdgeScroll" "0"

Option "VertEdgeScroll" "1"

Option "VertTwoFingerScroll" "0"

EndSection

By placing such options in individual files, you can easily manage your X configuration by sections.

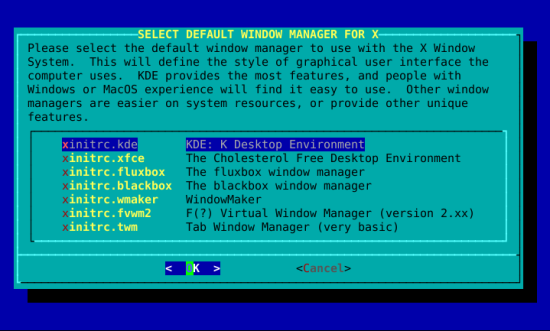

Choosing a Window Manager

Slackware Linux includes many different window managers and desktop environments. Window managers are the applications responsible for painting application windows on the screen, resizing these windows, and similar tasks. Desktop environments include a window manager, but also add task bars, menus, icons, and more. Slackware includes both the KDE and XFCE desktop environments and several additional window managers. Which you use is entirely your own decision, but in general, window managers tend to be faster than desktop environments and more suitable to older systems with less memory and slower processors. Desktop environments will be more comfortable for users accustomed to Microsoft Windows.

The easiest way to choose a window manager is xwmconfig(1), included with Slackware Linux. This application allows a user to choose what window manager to run with startx.

Setting Up A Graphical Login

By default, when you boot your Slackware Linux system you are presented with a login prompt on a virtual terminal. This is more than adequate for most people's needs. If you need to run commandline applications, you may login and do so right away. If you want to run X, simply executing startx will do that for you nicely. But suppose you almost exclusively use your system for graphical duties like many laptop owners? Wouldn't it be nice for Slackware to take you straight into a GUI? Fortunately, there's an easy way to do just that.

Slackware uses the System V init system which allows the administrator to boot into or change to different runlevels, which are really just different “states” the computer can be in. In fact, shutting down the computer is really only a case of changing to a runlevel which accomplishes just that. Runlevels can be rather complicated, so we won't delve into them any further than necessary.

Runlevels are configured in inittab(5).

The most common ones are

runlevel 3 (Slackware's default) and runlevel 4 (GUI). In order to tell

Slackware to boot to a GUI screen, simply open

/etc/inittab with your

favorite editor of choice. (You may wish to refer to one of the

chapters on vi or

emacs at this point.) Near the top, you'll

see the relevant entries.

# These are the default runlevels in Slackware: # 0 = halt # 1 = single user mode # 2 = unused (but configured the same as runlevel 3) # 3 = multiuser mode (default Slackware runlevel) # 4 = X11 with KDM/GDM/XDM (session managers) # 5 = unused (but configured the same as runlevel 3) # 6 = reboot # Default runlevel. (Do not set to 0 or 6) id:3:initdefault:

In this file (along with most configuration files) anything following a hash symbol # is a comment and not interpreted by init(8). Don't worry if you don't understand everything about inittab, as many veteran users don't either. The only line we are interested in is the last on above. Simply change the 3 to a 4 and reboot.

# These are the default runlevels in Slackware: # 0 = halt # 1 = single user mode # 2 = unused (but configured the same as runlevel 3) # 3 = multiuser mode (default Slackware runlevel) # 4 = X11 with KDM/GDM/XDM (session managers) # 5 = unused (but configured the same as runlevel 3) # 6 = reboot # Default runlevel. (Do not set to 0 or 6) id:4:initdefault:

Chapter Navigation

Previous Chapter: Process Control

Next Chapter: Printing

Sources

- Original source: http://www.slackbook.org/beta

- Originally written by Alan Hicks, Chris Lumens, David Cantrell, Logan Johnson