¡Esta es una revisión vieja del documento!

Tabla de Contenidos

El núcleo de Linux

¿Qué hace el núcleo?

Probablemente haya escuchado a la gente hablar acerca de compilar el núcleo o construir un núcleo, pero ¿qué es exactamente el núcleo y qué es lo que hace? El núcleo es el centro de su ordenador. Es la base del sistema operativo completo. El núcleo actúa como un puente entre el hardware y las aplicaciones. Esto significa que el núcleo es (normalmente) la única pieza de software responsable de ordenar alrededor de los componentes de hardware de su ordenador. Es el núcleo quien instruye a las unidades de discos duros para buscar un determinado flujo de datos. Es el núcleo quien indica a su tarjeta de red que transmita cambios rápidos de voltaje. Así como es el núcleo quien también escucha al hardware. Cuando la tarjeta de red detecta un ordenador remoto que envía información, reenvía esa información al núcleo. Esto hace que el núcleo sea la pieza más importante de software en su ordenador y la más compleja.

Trabajar con módulos

La complejidad de un núcleo de Linux actual es asombrosa. El código fuente para el núcleo pesa casi 400 MB sin comprimir. Hay miles de desarrolladores, centenares de opciones, y si todo estuviese construido junto, el núcleo pronto pasaría los 100MB de tamaño. Con el fin de mantener el tamaño del núcleo bajo (así como la cantidad de RAM necesaria para el núcleo), la mayoría de las opciones del núcleo se construyen como módulos. Usted puede pensar en estos módulos como controladores de dispositivo que pueden ser insertados o eliminados de un núcleo en ejecución cuando uno quiera. Verdaderamente, muchos de ellos no son controladores de dispositivo en absoluto, pero contienen soporte para cosas tales como protocolos de red, medidas de seguridad e incluso sistemas de archivos. En resumen, casi cualquier pieza del núcleo de Linux se puede construir como un módulo cargable.

Es importante darse cuenta de que Slackware manejará automáticamente la carga de la mayoría de los módulos. Cuando su sistema arranca,

udevd(8) se inicia y comienza a explorar el

hardware de su sistema. Para cada dispositivo que encuentra, carga el módulo adecuado y crea un nodo de dispositivo en /dev. Esto suele

significar que no tendrá que cargar ningún módulo para poder utilizar su

ordenador, pero a veces esto es necesario.

Entonces, ¿qué módulos se cargan actualmente en su ordenador y cómo lo hacemos para que se carguen y descarguen? Afortunadamente tenemos un conjunto completo de herramientas para manejar esto. Como habrá adivinado, la herramienta para enumerar los módulos es lsmod(8).

darkstar:~# lsmod Module Size Used by nls_utf8 1952 1 cifs 240600 2 i915 168584 2 drm 168128 3 i915 i2c_algo_bit 6468 1 i915 tun 12740 1 ... many more lines ommitted ...

Además de mostrarle qué módulos están cargados, muestra el tamaño de cada módulo y le dice qué otros módulos lo están utilizando.

Hay dos aplicaciones para cargar módulos: insmod(8) y modprobe(8). Ambos cargarán módulos y reportarán cualquier error (como cargar un módulo para un dispositivo que no está presente en su sistema), pero modprobe es preferido porque puede cargar cualquier dependencia del módulo. Usar cualquiera de las dos es sencillo.

darkstar:~# insmod ext3 darkstar:~# modprobe ext4 darkstar:~# lsmod | grep ext ext4 239928 1 jbd2 59088 1 ext4 crc16 1984 1 ext4 ext3 139408 0 jbd 48520 1 ext3 mbcache 8068 2 ext4,ext3

La eliminación de módulos puede ser un proceso complicado, y una vez más tenemos dos programas para eliminarlos: rmmod(8) y modprobe. Para eliminar un módulo con modprobe, necesitarás usar el argumento -r.

darkstar:~# rmmod ext3 darkstar:~# modprobe -r ext4 darkstar:~# lsmod | grep ext

Compilar un núcleo y por qué hacerlo así

La mayoría de los usuarios de Slackware nunca necesitarán compilar un núcleo. Los núcleos gigante y genérico contienen prácticamente todo el soporte que necesitará.

Sin embargo, es posible que algunos usuarios necesiten compilar un núcleo. Si el ordenador contiene hardware de última tecnología, un núcleo más nuevo puede ofrecer mejor soporte. A veces puede estar disponible un parche del núcleo que corrige un problema que está experimentando. En estos casos, una compilación del núcleo está probablemente justificada. Los usuarios que simplemente quieren la última y la mejor versión o quienes crean que usar un núcleo compilado personalizado les dará un mayor rendimiento, sin duda puede mejorar, pero es poco probable que realmente se noten cambios importantes.

Si aún piensa que compilar su propio kernel es algo que quiera o necesite hacer, esta sección debería guiarle a través de los numerosos pasos. Compilar e instalar un núcleo no es tan difícil, pero hay una serie de errores que se pueden hacer a lo largo del camino, muchos de los cuales pueden evitar que el ordenador arranque y causar una gran frustración.

El primer paso es asegurarse de que tiene el código fuente del núcleo instalado en su sistema. El paquete fuente del núcleo está incluido en el conjunto de discos

“k” en el instalador de Slackware, o puede descargar otra versión de http://www.kernel.org/.

Tradicionalmente, la fuente del núcleo se encuentra en

/usr/src/linux, un enlace simbólico que

apunta a la versión específica del núcleo utilizada, pero esto no está de ninguna manera

grabado en piedra. You can place the kernel source code virtually anywhere

without encountering any problems.

darkstar:~# ls -l /usr/src lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 14 2009-07-22 19:59 linux -> linux-2.6.29.6/ drwxr-xr-x 23 root root 4096 2010-03-17 19:00 linux-2.6.29.6/

The most difficult part of any kernel compile is the kernel

configuration. There are hundreds of options, many of which can

optionally be compiled into modules. This means there are thousands of

ways to configure a kernel. Fortunately, there are a few handy tricks

that can keep you from running into too much trouble. The kernel

configuration file is .config. If you are very

brave, you can manually edit this file with a text editor, but I highly

recommend you use the kernel's built-in tools for manipulating

.config.

Unless you are very familiar with configuring kernels, you should

always start with a solid base configuration and modify it. This

prevents you from skipping an important option that might force you to

compile the kernel again and again until you get it right. The best

kernel .config files to start with are those used

by Slackware's default kernels. You can find them on your Slackware

install disks or at your favorite mirror in the

kernels/ directory.

darkstar:~# mount /mnt/cdrom darkstar:~# cd /mnt/cdrom/kernels darkstar:/mnt/cdrom/kernels# ls VERSIONS.TXT huge.s/ generic.s/ speakup.s/ darkstar:/mnt/cdrom/kernels# ls genric.s System.map.gz bzImage config

You can replace the default .config file easily by

copying or downloading the config file for the

kernel you wish to use as a base. Here I am using Slackware's

recommended generic.s kernel for a base, but you may wish to use the

huge.s config file. The generic kernel builds more things as modules

and thus creates a smaller kernel image, but it usually requires the

use of an initrd.

darkstar:/mnt/cdrom/kernels# cp generic.s/config /usr/src/linux/.config

config to

/usr/src whatever

.config file was already present will be used

instead.

If you want to use the configuration for the currently running kernel

as your base, you may be able to locate it at

/proc/config.gz. This is a special kernel-related

file that includes the entire kernel configuration in a compressed

format and requires that your kernel was built to support it.

darkstar:~# zcat /proc/config.gz > /usr/src/linux/.config

Now that we've created a solid base configuration, it's time to make any configuration changes we want. The entire kernel build process from configuration to compilation is performed with the make(1) command and special arguments to it. Each argument performs a different function.

If you are upgrading to a newer kernel release, you will definitely

want to use the oldconfig argument. This will step through

your base .config and look for missing elements

that usually indicates that the new kernel release contains additional

options. Since options are added at virtually every kernel release,

this is generally a good thing to do.

darkstar:/usr/src/linux# make oldconfig

scripts/kconfig/conf -o arch/x86/Kconfig

*

* Restart config...

*

*

* File systems

*

Second extended fs support (EXT2_FS) [M/n/y/?] m

Ext2 extended attributes (EXT2_FS_XATTR) [N/y/?] n

Ext2 execute in place support (EXT2_FS_XIP) [N/y/?] n

Ext3 journalling file system support (EXT3_FS) [M/n/y/?] m

Ext3 extended attributes (EXT3_FS_XATTR) [Y/n/?] y

Ext3 POSIX Access Control Lists (EXT3_FS_POSIX_ACL) [Y/n/?] y

Ext3 Security Labels (EXT3_FS_SECURITY) [Y/n/?] y

The Extended 4 (ext4) filesystem (EXT4_FS) [N/m/y/?] (NEW) m

Here you can see that the new kernel I am compiling has added support for a new filesystem: ext4. oldconfig has gone through my original configuration, kept all the old options exactly as they were set, and prompted me on what to do with new options. Typically it is safe to choose the default option, but you may wish change this. oldconfig is a very handy tool for presenting you with only new configuration options, making it ideal for users who simply have to try out the latest kernel release.

For more serious configuration tasks, there are a multitude of options. The linux kernel can be configured in three primary ways. The first is config, which will step through each and every option one by one and ask what you would like to do. This is so tedious that hardly anyone ever uses it anymore.

darkstar:/usr/src/linux# make config scripts/kconfig/conf arch/x86/Kconfig * * Linux Kernel Configuration * * * General setup * Prompt for development and/or incomplete code/drivers (EXPERIMENTAL) [Y/n/?] Y Local version - append to kernel release (LOCALVERSION) [] -test Automatically append version information to the version string (LOCALVERSION_AUTO) [N/y/?] n Support for paging of anonymous memory (swap) (SWAP) [Y/n/?]

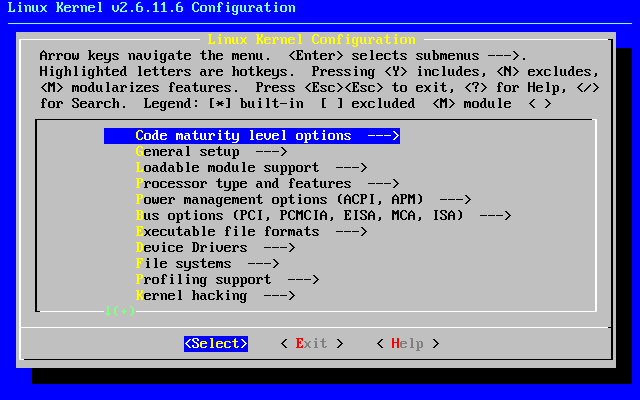

Fortunately, there are two much easier ways to configure your kernel, menuconfig and xconfig. Both of these create a menu-driven program that lets you select and de-select options without having to step through each one. menuconfig is the most commonly used method, and the one I recommend. xconfig is only useful if you are attempting to compile the kernel from a graphical user interface within X. Both are so similar however, that we are only going to document menuconfig.

Running make menuconfig from a terminal will present you with the friendly curses-driven interface you see below. Each kernel section is given its own submenu, and you can navigate with the arrow keys.

Once you've finished configuring the kernel, it's time to begin compiling it. There are many different methods for this, but the most reliable is to use bzImage. When you pass this argument to make, the kernel compilation will begin and you will see lots of data scroll through the terminal until either the compile process is complete or a fatal error is encountered.

darkstar:/usr/src/linux# make bzImage scripts/kconfig/conf -s arch/x86/Kconfig CHK include/linux/version.h CHK include/linux/utsrelease.h SYMLINK include/asm -> include/asm-x86 CALL scripts/checksyscalls.sh CC scripts/mod/empty.o HOSTCC scripts/mod/mk_elfconfig MKELF scripts/mod/elfconfig.h HOSTCC scripts/mod/file2alias.o ... many hundreds of lines ommitted ...

If the process ends in an error, you should check your kernel

configuration first. Compile errors are usually caused by a fault

.config file. Assuming everything went alright,

we're still not entirely finished, as we need to build the modules.

darkstar:/usr/src/linux# make modules CHK include/linux/version.h CHK include/linux/utsrelease.h SYMLINK include/asm -> include/asm-x86 CALL scripts/checksyscalls.sh HOSTCC scripts/mod/file2alias.o ... many thousands of lines omitted ...

If both the kernel and the modules compiles finished sucessfully, we're

ready to install them. The kernel image needs to be copied into a safe

location, typically the /boot directory, and you

should give it a unique name to avoid overwriting any other kernel

images located there. Traditionaly kernel images are named

vmlinuz with the kernel release and local version

appended.

darkstar:/usr/src/linux# cat arch/x86/boot/bzImage > /boot/vmlinuz-release_number-local_version darkstar:/usr/src/linux# make modules_install

Once these steps have been completed, you will have a new kernel image

located under /boot and a new kernel modules

directory under /lib/modules. In order to use

this new kernel, you will need to edit lilo.conf,

create an initrd for it (only if you need to load one or more of this

kernel's modules to boot), and run lilo to

update the boot loader. When you reboot, if all went according to plan,

you should have an option to boot with your newly compiled kernel. If

something went wrong, you may be spending some time fixing the problem.

Chapter Navigation

Previous Chapter: Keeping Track of Updates

Sources

- Original source: http://www.slackbook.org/beta

- Originally written by Alan Hicks, Chris Lumens, David Cantrell, Logan Johnson